Finding Value in Loss

Written in a TED Talk style to share a heavy topic with warmth and clarity.

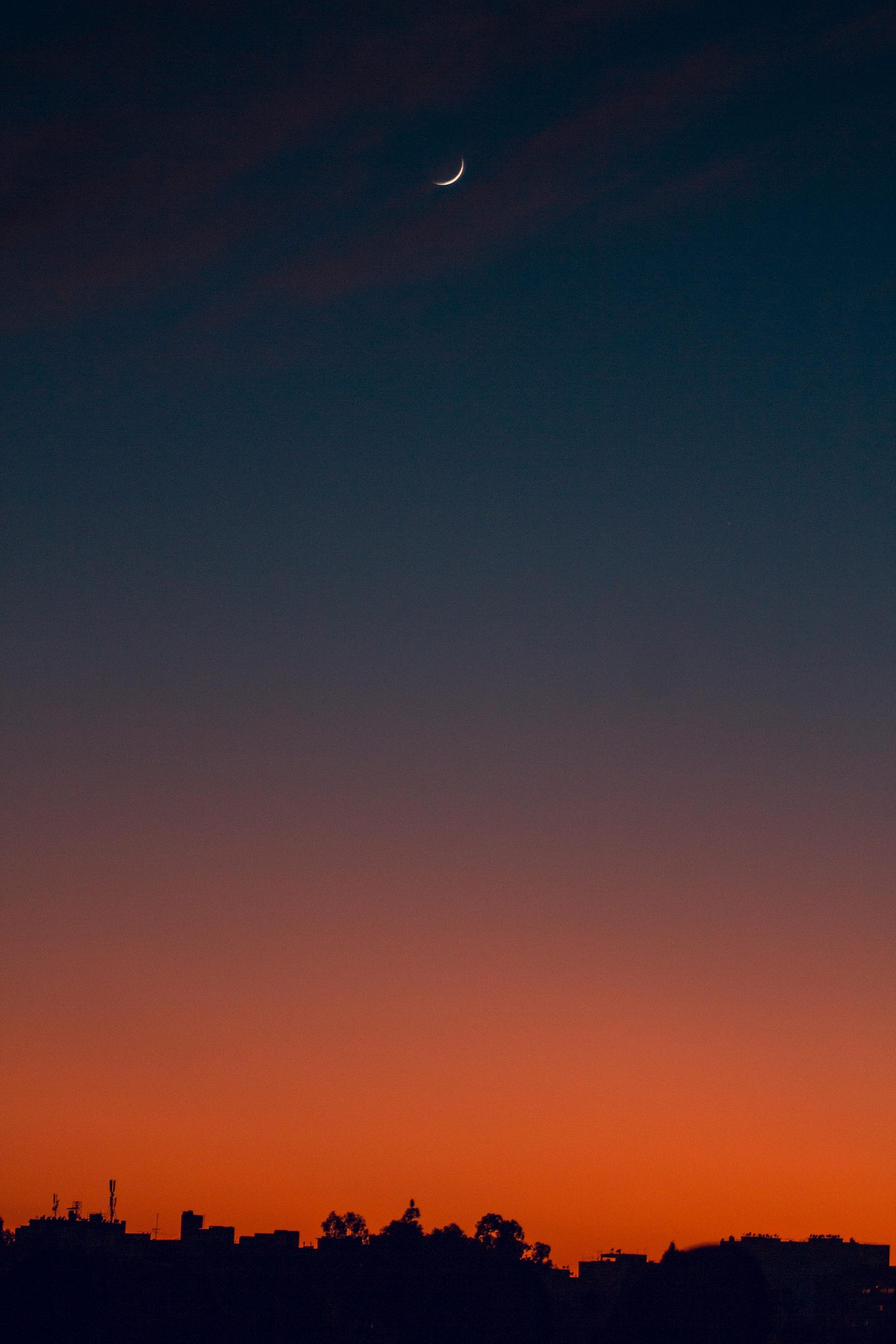

Photo by Brakou Abdelghani: https://www.pexels.com/photo/silhouette-of-trees-during-sunset-1723637/

Good day, everyone. Today I'd like to talk about "loss" from my personal experience.

Is losing something truly terrifying? Of course, there are things we don't want to lose—safety, property, dignity. But the meaning of loss is something I was forced to contemplate at just 12 years old.

Note: As a native Japanese thinker writing in English, I use AI tools to help bridge cultural and linguistic gaps - similar to how a musician might use technology to arrange their compositions. All ideas, perspectives, and cultural insights remain uniquely mine.

It was a morning during my sixth grade year. The rain shutters that should have been open remained closed. Finding this strange, I called downstairs on the intercom, and my mother responded, "Stay there, I need to explain something to you."

My father had died.

A traditional Buddhist funeral would be held in our home. My father, who just yesterday had said "I'm heading out" as he left, was now in a wooden coffin placed in our living room. For 12-year-old me, it was an utterly surreal scene.

I didn't even have the luxury to grieve. In Japanese culture, the responsibility of the eldest child is significant. Relatives from all sides told me, "You're the eldest, you need to be strong." Even my mother's cousins, people I had never met before, came specifically to tell me the same thing. "Yes, I need to be strong," I thought to myself.

At 12, I couldn't understand why my father died—I wouldn't learn the reason until I was 17. But there was one thing I could comprehend: "Dad will never come home and say 'I'm back' again."

This was how a 12-year-old boy understood "death" in his own words.

Our family lost one person who would come home saying "I'm back." Still, we continued living as a family—my mother, my younger sibling, our pets, and me.

I'd like us to consider the difference between "disappearing from this world" and "never being able to meet again." In times before modern communication, going to a foreign country meant you might never see someone again. Yet you could still think, "Even though we can't meet, they're living happily somewhere far away."

Whether it's Heaven in Christianity or the Pure Land in Buddhism, different names for "paradise" have been passed down through our cultures. Weren't these concepts born from our wish that "those we can no longer meet are doing well somewhere"? Is this too much imagination? From my experience, such thoughts seem perfectly natural.

Losing something, parting with someone, or disappearing—these are certainly negative experiences. But since we aren't eternal beings, such events are inevitable in our lives.

What I realized is this: losing something worthless causes no pain. If losing something makes you suffer, it must have been irreplaceably precious to you. In other words, having met something worth grieving over when lost—isn't that itself a fortunate thing?

"Because farewell will surely come one day, cherish the people you care about now"—this resonates with the Japanese concept of "ichigo ichie," treasuring each encounter as it may never come again.

Even events typically seen as negative can become our assets in life. This is what my experience at 12 years old taught me.

"Why are the rain shutters still closed?"

"It's time for school."

"You're the eldest, be strong."

"Ah, this person will never come home again."

Though a 12-year-old's thoughts have their limitations, within those limitations, I believe I found something universal.

Finally, I want to share this: If you have someone who comes home saying "I'm back"—whether a person, a dog, a cat, or a bird—love them with all your heart while you can. And if they're no longer with you, cherish those memories.

What do you think? Thank you.

About the Author

Amazon Author Page

https://www.amazon.com/stores/author/B0DL3S6CMB/about

note.com(In Japanese)

https://note.com/karasu_toragara

AI Art on Instagram

https://www.instagram.com/karasu_toragara/

More Writings on Medium

https://medium.com/@trgr.karasu.toragara

It is amazing, that we cling to the belief, that as the sun rises every day, life would be a constantly repeating, renewing endless rythm.

“But you will die”

“Yes, of course, in the end”

“So imagine what happens, if your friend dies”

So we make a step to begin to think:

“what … if”

And every time something dramatically happens, we are surprised and afterwards much wiser then before.

Again and again.

Until we really deeply accept and rephrase the dialog:

“But you will die”

“Yes, of course, any time”

“So imagine what happens, as soon as your friend will die."

Then we have the chance to really live in the NOW and conciously do all you do now. Talk now. Write now. Smile now. Thank now. Laugh now.

This is a beautiful piece of writing. I had not heard the term "ichigo ichie" before and I love the idea of connecting it to grief.

I practice many forms of meditation, and I've recently been learning about tea ceremony as a way of contemplating impermanence.

I aspire one day to always view the world as ichigo ichie, and to cherish every moment of my life.

I hope I've used that term correctly. Thank you for sharing it. Thank you also for being willing to share painful parts of your life.